If we’re talking about reforming police departments, maybe we should be talking about rebranding them, as well.

Serious, important questions are being asked about how our police forces allocate the tremendous financial resources they’re given. And when peaceful protests are met with a militarized response, what are we to make of that? What has become of our civilian police force – do they see themselves as part of us, for us, or do they see themselves as something apart, an occupying force aligned against us? What are their motivations and incentivizations? And we need to ask the officers themselves: is this even what you signed up for?

Cops have a tough job, and the best thing so far to come out of this is a frank discussion of just how odd it is that we expect to solve every societal problem we encounter with a call to 911. It turns out, an armed police officer trained to apprehend dangerous criminals isn’t necessarily the best person to deal with a mental health crisis, rape, or maybe even something as relatively criminally trivial as passing a phony $20 bill. So what is the highest and best use for our police forces? Other countries have approaches to policing that don’t result in as much violence, so what are they doing that we could learn from? As we say in our business, how can we help cops in the US find and operationalize their “Why?”

Chromium is a branding firm. We’re not a law enforcement training outfit. We’re not professional criminologists. But still, our training in consumer perception does have validity in these conversations. Because the things you’ll likely find written on almost every police department website are the very same things you’ll find in any corporate brand strategy:

Mission, vision, values, persona, customer needs statement, proof points, narrative – they’re all there in various incarnations. Different police forces even have their own brand essence. NYPD has the hard-boiled beat cop in their DNA. Your local sheriff probably still “wears” the ghost of the lawman’s white hat from the Old West. Are these classic brand essences helpful? Or are they standing in the way of better policing?

Then there are the brand expressions: everything from the way they display the word POLICE on the sides of their cars (some are modest, some solid and authoritative, others taking bold italics, gradient effects, and striping to macho extremes). There are the taglines “To Protect and Serve,” “Safety and Service” written on the fenders. There are the different uniforms and hats. There are cool cops on bicycles and a totally different kind of cop on a Harley Davidson motorcycle. Cops on horseback can seem either impressively reassuring and friendly if you see them in the park, or terrifyingly Medieval if they’re trampling protestors.

So, if a police force has everything that comprises a brand strategy, and goes to great length to project a brand image, who can possibly say that branding isn’t a key part of policing – and quite possibly a key part of what has gone so wrong in so many of our police departments today?

A brand strategy informs many things about an organization, not just what it looks like, but what kind of talent it attracts and hires, how it communicates and interacts with its customers – a whole range of activities and operations revolve around such things as mission, vision, and values. Could it be that in police departments that are exhibiting excessive force or bias, that these important core tenets are either poorly communicated, poorly supported, or simply inauthentic? Perhaps they’re legit, but have not been effectively operationalized.

A quick look at our own local SFPD website provides a telling clue as to how militarization can weave its way even into a very progressive police department like San Francisco. As police forces go, they have clearly been engaged in a close examination of their brand and culture as evidenced by the number of minorities and women both on the force and in leadership positions, as well as transparent and this publicly-available “Strategic Plan 1.0” document.

But instead of calling the components of their brand strategy things like mission, vision, and values, they use terms that do have a certain military precision to them: What we would call a mission (itself a relatively militaristic term), SFPD labels a “Strategy Statement.” What in a Chromium brand framework is known as core values (which drive how a brand operates) are termed “Strategic Initiative Clusters.” The “clusters” themselves are positive and inspiring (you can read them here), but it’s difficult to hear the word “cluster” and not have your mind follow on with either “-bomb” or “-f**k.” Plus, when something is touted by leadership as a “core value,” activities that run counter to those core values are clearly egregious violations of trust, whereas not following the “strategic initiative cluster” sounds more like a minor procedural error.

The Wilmington, NC police department, which has been embroiled in controversy since three officers were caught on camera espousing violently racist views, and for which those officers were immediately fired, has what they call a “mission statement” posted on its website:

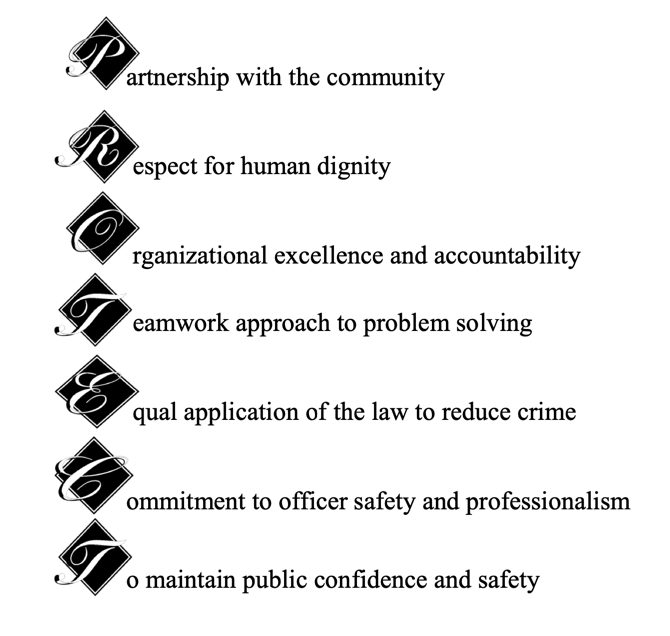

Clever, how they managed to spell “PROTECT” with the initial letter of each sentence. Odd, that these are really more a set of core values, describing how the department operates, not really a mission, per se, which should be a statement about what the organization is trying to achieve. Still, even though the three cops who got fired clearly had never assimilated these principles into their work lives, top brass showed real commitment to them by immediately terminating these proverbial bad apples once their conduct came to light. But if these principles are so important to this department, how did people holding those views get hired in the first place? Some sort of breakdown plainly occurred, and it’s likely due to the brand receiving lip service rather than being an actual touchstone for the department’s way of being. In Chromium parlance, they simply weren’t living the brand.

Or look at this scenario in Philadelphia, as captured by a report for the Philadelphia Enquirer moments she was arrested, despite clearly identifying herself as a member of the press:

Does it make you feel safer to know that your police department has a “COUNTER TERRORISM” team that can be deployed against its own citizens? And what’s with the black combat outfits and the body armor? What these and other examples of police “branding” clearly show is that militarization has indeed crept into what we believe should be a much more modest, non-threatening display of civilian law enforcement ideals. In this remarkable video, the New York Times analyzed how quickly breakdowns in civility can happen when the “brand positioning” and “brand expressions” (our words) of policing change from civilian to military.

Chromium believes that having a clear, thoughtful brand strategy which guides all expressions of a police department’s brand – from how the cars are signified to what kind of uniform the officers wear, and the way they interact with the public – can be part of realigning the public perception of the police from being an opposing force to being a protective one. Some departments understand this and have made great strides towards developing a brand strategy that is more allied with the civilians they protect and serve. Others have a ways to go.

Recent Comments